Coal miner's (great-grand)daughter

Memento Mori oracle cards from Black and the Moon

When I was little, my grandfather told me his dad died in the coal mines. I regret not having the foresight to ask more questions about his parents, but I do remember small details, like the way his mother wore her hair (French twist).

I was extremely close with my grandfather and grew up admiring not only him but the art he created. Mining was a big theme in his writing and painting, and since his work was brimming with the spirit of southwestern Pennsylvania, they became intertwined for me.

I realize now that I grew more curious about my great-grandfather’s identity as I became more self-assured in my own. The small bits of info I retained from childhood started nudging at me as a new parent (especially during the most desperate parts) and I started to hear his voice.

You’d think in this case I’d hear more of a calling from his wife, my great-grandmother. After all, she was the mother of five children by age 25 and living in a coal town under intense hardship. I’m sure she has a lot to say. But my great-grandfather always had more of a pull. And I think it’s because he was lonely.

While it would be nearly impossible to truly depict the struggle of a miner’s family, if you’ve ever read The Hunger Games (my favorite series), you know that Katniss grew up in an impoverished coal town with her mom and little sister. Her mother was mostly absent, having never recovered from the grief of losing her husband to a mine disaster. And while her character serves to illustrate how Katniss was forced to grow up too early and fend for herself, I empathized with her mom’s despondency. I don’t know if I’d find the strength.

An article from the June 23rd, 1888 edition of Harper’s Weekly Magazine illustrates the dire conditions of a Pennsylvania coal field:

There is no human existence more purely animal than that which moves on from the cradle to the grave in the coal villages of Pennsylvania. Early in the morning the men and boys go to their work in the mines. The women wait all day anxiously for their return, prepared to hear at any moment of a dreadful catastrophe from the explosion of fire-damp or a cave in. [Source]

My great-grandfather Michael arrived in New York City in 1912 (at age 19). My friend Cristina discovered that he departed from Galicia, Spain on a ship called the Queen Louise. He traveled alone. His wife, my great-grandmother Mary, also arrived the same year (likely with family as she was 14, but I’m not certain). They married shortly after in 1916 (he was 23 and Mary was 18) in a Greek Orthodox church near Pittsburgh.

From there, he started working for Ford Collieries Company in nearby Curtisville. His mine was called “No. 3. Bairdford.” The family lived on a coal patch (i.e. town) and had five kids in quick succession. At the time, Pennsylvania had more coal patches than any other state in the country. Most were inhabited by recently-arrived immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

In addition to the rows of frame houses, patches typically had a church and company store, but not much else. I’ve always been especially interested in domestic life during this time. An excerpt from Reminiscences of John Maguire describes the inside of the homes in more detail:

Each was equipped with a coal stove, being a step stove, also a bedstead made of square timber, by the colliery carpenter, a deal table, also a few benches. They paid $4 a month for the houses and got their coal “thrown in.” Sometimes a new family would arrive and take possession of a bare, empty house. In the evening, after the men came from work, the older residents would call upon the new comers. Tom Rutledge, one of the miners would go there with his fiddle and they would have a dance in the newly occupied house the same night. This was their method of welcoming the stranger in their midst.

It also details the village-like qualities of the towns:

Women baked bread in communal ovens, washed clothing in communal washtubs, and cared for one another's children and for those in need among neighbors and the extended family. Women and children worked together to harvest food from backyard vegetable gardens, which provided an important source of additional food. [Source]

Even though I’m constantly lamenting the fact that I don’t have the privilege of communal childcare, this was obviously an extremely difficult way of life. Aside from the constant stress and struggle of such backbreaking labor, there must have been a great deal of uncertainty, isolation, and fear. Alcoholism was rampant. The documentary The Mine Wars provided more insight into the life of a miner’s wife:

Women prepared the food that the miners brought to work, and they cleaned the miner's clothes. They managed to support their children on what little pay the miner brought home, often dealing with the monopolistic prices at the company store. Depending on the coal camp, they were tasked with hauling water from nearby creeks or water pumps up to their homes for drinking and bathing. […] These were women who had to deal with harsh circumstances, and they themselves had to have a certain type of toughness, not just physical toughness, but a psychological toughness. [Source]

Life was equally brutal for the kids. They weren’t provided any kind of education and worked to earn additional income for the family. I wish I’d asked my grandfather if he remembered any of it. From the Harper’s Weekly Magazine article:

It is illegal in Pennsylvania to employ children in the mines; but the law is constantly broken, and boys of very tender years open and shut the heavy doors in the galleries when the cars pass in and out. The occupation is dangerous, and many of the boys lose their lives. The girls are sent to distant places to work in the mills. [Source]

Many of these themes are also apparent in the folk music of the region, which has its own unique flavor compared to the southern Appalachian states. Here’s a verse I love from a collection of folk songs entitled Minstrels of the Mine Patch and Coal Dust on the Fiddle:

Come all ye good fellows, so young and so fine,

Oh seek not your fortune in a dark, dreary mine,

It will form a bad habit and seep in your soul,

Till the stream of your blood runs as black as the coal.

It's dark as a dungeon and damp as the dew,

Where the dangers are doubled and the pleasures are few.

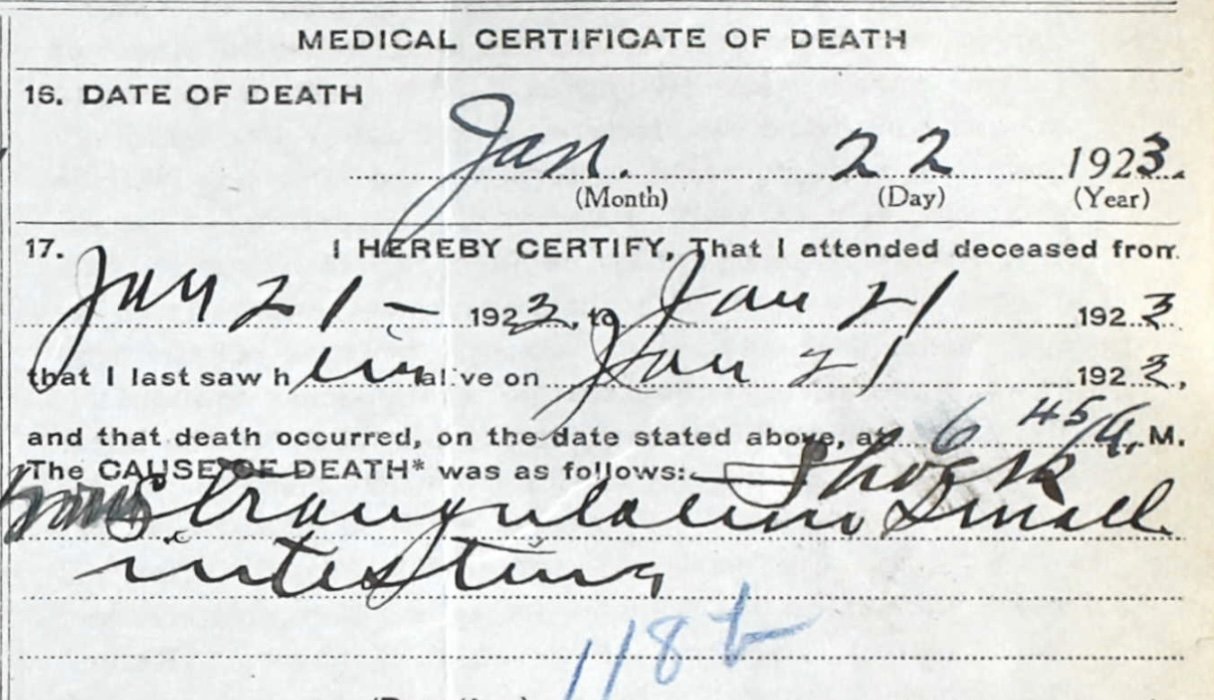

I didn’t start looking for specific family information in earnest until about two years ago when I finally started building my tree. As expected, I couldn’t find any record of my great-grandparents pre-America, and unfortunately, not much more after (and no pictures at all). Over time I shared quick notes in my Instagram stories when I learned something new, but it all culminated with the discovery of his cause of death and a visit to his grave.

I’d already tried on several occasions to figure out his cause of death but could never find a record of a mine accident on or around the date he passed. This was especially frustrating since it seemed like mining disasters were otherwise very well-documented.

I finally got some insight after locating his death certificate through the Carnegie Library. I took a screenshot and sent it to my husband, indicating that I couldn’t read the handwriting. Chuck deciphered it immediately.

Shock. Strangulation small intestine. Likely a hernia.

So he did die in the coal mines, just not from a mining accident. I can’t imagine having to break that news to his family.

I subsequently set about finding his resting place. The location of the cemetery was easy (Union Cemetery in Arnold, PA) but I didn’t have high expectations for the actual stone. While it seemed like parts of the graveyard were being maintained, many of the markers were crumbling, faded, or completely sunken.

But truly, as soon as I left the car, I was pulled in the right direction. It felt like I’d already been there but had to stop and greet some neighbors on the way. While it’s always heartbreaking to encounter neglected graveyards, many of the stones were so personal and beautiful and I was happy to be able to spend time with them, especially since many are nearly gone.

And then there he was. The inscription was faded but (luckily) recognizable. I could make out his name and the years of his birth and death.

I knelt pretty quickly and put both of my hands on his headstone. I wondered about the last time someone touched it intentionally. Was it family? (My great-grandmother remarried soon after his death, being so young and widowed with five children, so she’s buried elsewhere.)

I was emotional for a minute thinking about him there alone. Did he feel like his life was forgotten?

Then something cool happened. When I took my hands away from his headstone and looked down, I saw a sprig of juniper and felt a shift. I looked up at the hill in front of me and really took in the view. I was kneeling in the same spot where Mary knelt almost exactly 100 years earlier as a widow at 25. My grandfather, her youngest, was 2 at the time. She must’ve been utterly anguished. I felt a connection with her then.

Juniper has always been a favorite tree and ally (along with oak and pine). I scanned the cemetery for the tree that produced this stem and didn’t see one nearby. I knew it was meant for Mary, so I took his message with me. He probably never got to say goodbye. Delivering it to her will be a gift for both of us.

To learn more about me and my Appalachian folk practice, including info on folk witchcraft, mountain magic, and hearthcraft, please visit gritchenwitch.com or join my Patreon at patreon.com/gritchenwitch.

Follow: Instagram | TikTok | Facebook | Shop | Etsy | Patreon